Collection PLUS Highlights Latent Appeal of Works in Collection

Morizono Atsushi, Chief Curator, Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum

An Exhibition Illuminating Another Side of Kamoi Rei

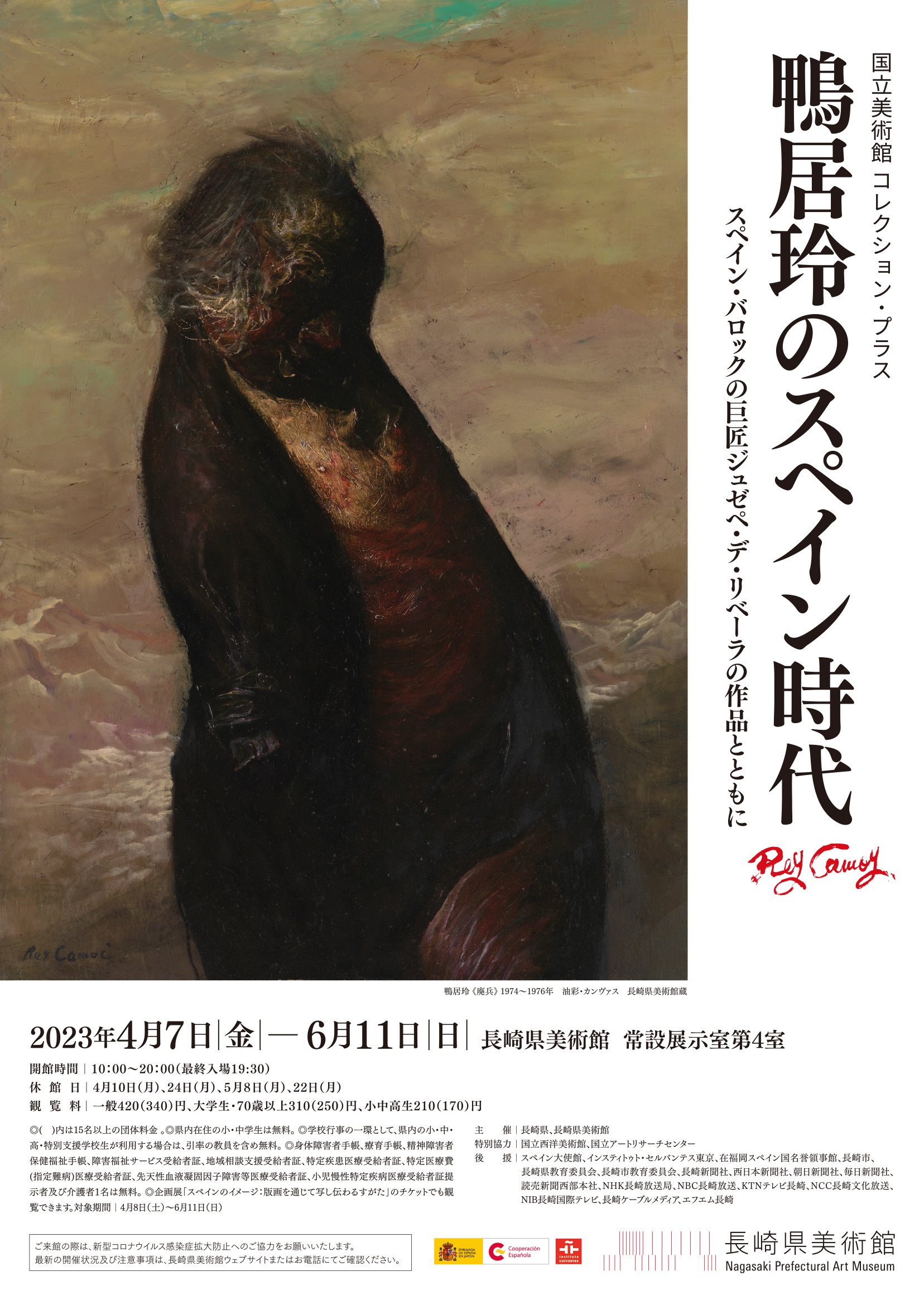

Flyer for Rey Camoi’s Spanish Period

Kamoi Rei, an Artist Connected to both Nagasaki and Spain

Kamoi Rei was a painter associated with Nagasaki, with his registered domicile in what is today Hirado City, Nagasaki Prefecture. Due to this connection, Nagasaki Prefecture has actively acquired Kamoi’s works since he was alive, and has worked with his sister Yoko to conduct research on this artist with strong regional ties. Meanwhile, the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum is known for its focus on Spanish art and has organized numerous exhibitions showcasing it over the years. In recent years, the museum has also paid increasing attention to Japanese artists who studied in Spain, from the perspective of cultural exchange between the two nations. With his experience of living in Spain, Kamoi Rei is of enormous importance to us as both an artist related to Nagasaki and a Japanese artist who studied in Spain.

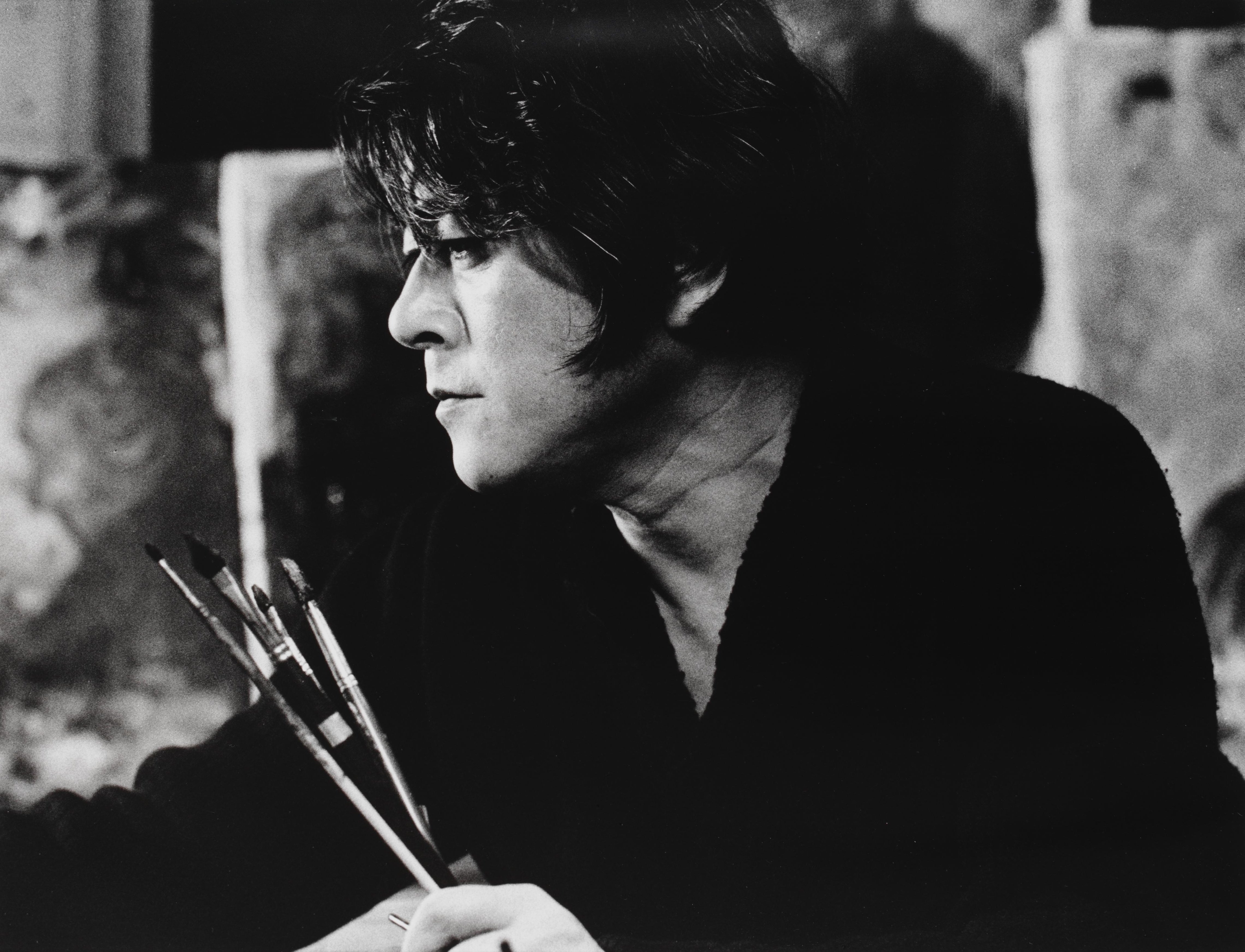

Portrait of Kamoi Rei (c. 1974). Photograph by Inoue Hakudo

Kamoi Rei is a relatively well-known painter, and from his death until the present day, large-scale retrospectives of his work have been held approximately every five years. In these retrospectives, his works from throughout his career are often presented in chronological order. However, with this exhibition our goal was to take a unique approach specific to the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum’s areas of focus, highlighting his “Spanish Period” and exploring new aspects of his work.

Kamoi’s Spanish Period

In February 1971, Kamoi Rei traveled to Spain, where he was to spend approximately three years and eight months. Notably, in the summer of 1971 he moved to Valdepeñas, a small town in the La Mancha region of central Spain, where he arrived at what is regarded as the peak of his career. His series portraying local villagers, featuring tropes such as “the old man” and “the drunkard,” captured a full range of human emotion on canvas and stands as the pinnacle of his artistic achievements. It is crucial to note that in the early 1970s, when Kamoi resided there, Spain was a closed society still under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Nonetheless, Kamoi’s engagement with the unique culture and people of Spain seemed to unleash a burst of creative energy that led to prolific output.

It is known that when Kamoi was living in Madrid, he was a frequent visitor to the Museo Nacional del Prado. There he was able to view the works of the Spanish Baroque painters and other masters such as Francisco José de Goya (1746-1828). It appears that he intuited something in the world of their works that resonated with his own aspirations. Among them, he was particularly drawn to Jusepe de Ribera, one of the most prominent painters of the golden age of the Spanish empire. Kamoi was able to immerse himself in the spirit of the Spanish people, viewing numerous works in museums across the country, including the Museo Nacional del Prado, and interacting on a warm human level with local people in Valdepeñas. The goal of this exhibition was to show that Kamoi drew much closer to the heart of Spanish culture and art than has previously been acknowledged.

The Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum and the Museo Nacional del Prado

Now I would like to turn to the relationship between the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum and the Museo Nacional del Prado. The Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum opened in 2005, and the year before that, in 2004, it signed a memorandum of understanding to promote friendship and cooperation with the Museo Nacional del Prado. Also, in 2009 the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum established a policy of dispatching curators to the Museo Nacional del Prado for research purposes every few years, and I had the privilege of being the first curator dispatched to the Museo Nacional del Prado, where I underwent training for about a month. While the purpose was not direct study of the works of old masters, during the training I was at liberty to enter the galleries of the Museo Nacional del Prado and enjoy Spanish art at my leisure, and looking back on it now, those were truly blissful days. On weekends I went on trips to various parts of Spain, visiting numerous museums and churches where I encountered Spanish art that remains vividly etched in my memory to this day.

The author in the Plaza Mayor, Madrid, while undergoing training at the Museo Nacional del Prado in 2009.

“What Would Ribera’s and Kamoi’s Works Look Like Side by Side?”

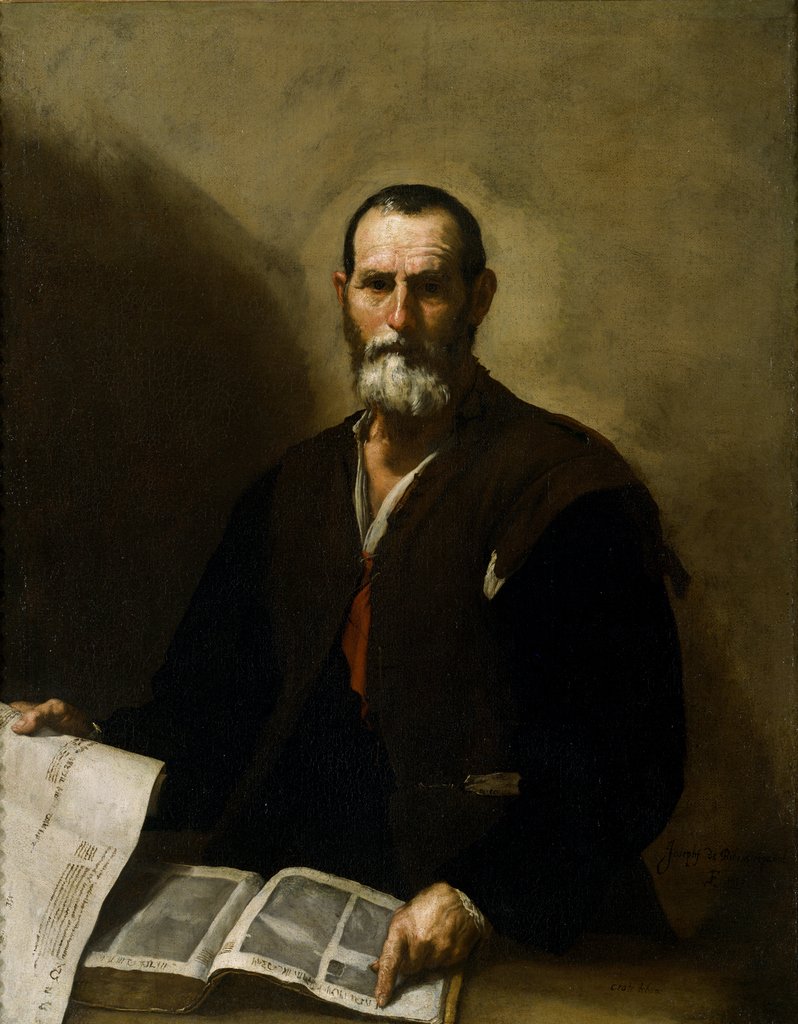

After this I took many more trips to Spain for exhibition preparations and so forth, and felt I was beginning to understand Spanish art little by little. As time passed, I found myself wondering, “what would Ribera’s and Kamoi’s works look like side by side?” And recently, we were lucky enough to receive a proposal from the National Center for Art Research that offered an unparalleled opportunity to turn my dream into reality. The painting Philosopher Crates, in the collection of the National Museum of Western Art, was painted with a contemporaneous old man as a model, and can be called a classic example of Ribera’s work. Like the paintings portraying saints and philosophers that Kamoi saw at the Museo Nacional del Prado, this painting clearly embodies Ribera’s distinctive artistic philosophy.

Jusepe de Ribera, Philosopher Crates, 1636, collection of the National Museum of Western Art

What They Looked Like Side by Side

It has repeatedly been noted in past exhibition catalogues that Kamoi learned a great deal from Ribera, but this is the first time their works have been exhibited side by side. At the venue, Ribera’s painting was placed in the center of the room, flanked by four of Kamoi’s works from his “pre-Spanish period” and five from his “Spanish period.” To be honest, before seeing these in person I could not predict what the effect of presenting their works together would be. However, when I looked around the venue, the influence of Ribera on Kamoi’s Spanish-period works was clear. Techniques of creating pictorial space, particularly that of casting spotlight-like illumination on the faces of subjects, testify to Kamoi’s allegiance to Ribera’s style. Also, Kamoi’s choice of marginalized subjects, such as the elderly, beggars, and wounded soldiers, connects to themes found in Spanish painting from the 19th century onwards. It became evident that during this period, Kamoi was even more closely aligned with Spanish art than we had imagined.

Installation view of Rey Camoi’s Spanish Period, 2023, Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum

Japanese Artists Who Studied in Spain

Here I would like to make it clear that the purpose of this exhibition was not to demonstrate that Kamoi was under the sway of Ribera in terms of technique or mindset. Rather it aimed to show, through specific Spanish art, what Kamoi absorbed while immersing himself in the atmosphere of Spain. More broadly speaking, it also invites us to consider what postwar Japanese artists sought when they traveled to Spain, then considered a remote backwater of Europe.

During Kamoi’s years in Spain, he interacted with numerous young Japanese painters who were studying in Madrid, including Wada Yoshihiko (1940-2016), Yabuno Ken (b. 1943), Kato Rikinosuke (b. 1944), and Ichihashi Yasuji (1948-2019), all of whom I had the opportunity to interview. Kamoi was apparently particularly apt to approach painters who were making copies after works in the Museo Nacional del Prado. It was not an entirely equal relationship of fellow artists and compatriots, as Kamoi already held a solid position in Japan’s Western-style painting world and all of these painters were his juniors, but he had a powerful impact on those artists who visited the studio where he turned out one masterwork after another. Kamoi is a figure of great significance from the vantage point of Japanese painters’ reception of Spanish art.

The Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum is considering organizing future exhibitions featuring Japanese artists who studied in Spain, and this exhibition served as a crucially important stepping stone for this endeavor.

The Exhibition in Retrospect

This exhibition was a rare opportunity to reveal new aspects of familiar works from the collection. Despite the limitation of the comparative display to just one borrowed work, I believe it was certainly sufficient to highlight the latent appeal of works in our collection.

In closing, I would like to express my most heartfelt gratitude to the staff of the National Center for Art Research, the researchers at the National Museum of Western Art, and everyone else whose involvement helped in myriad ways to make this exhibition possible.

Installation view of Rey Camoi’s Spanish Period, 2023, Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum

*Collection PLUS is a new initiative led by the National Center for Art Research. Its goal is to leverage the collections of the national museums so as to enrich exhibitions at regional art museums.

More details are here→