Initiatives for People with Hyperesthesia Symptoms

Head of ABLE ART JAPAN/

DEAI Research Lab. member

Shibasaki Yumiko

The author directing a program for mutual enjoyment with people with partial or full visual impairment (far right)

In this DEAI* Research Report series, DEAI Research Lab. members present accessibility case studies focused on museums.** In this article, Research Report 4, Shibasaki Yumiko of ABLE ART JAPAN writes about initiatives that an exhibition conducted oriented towards people with symptoms of hyperesthesia 1) . In this case study, the author discusses essential overall environmental arrangements that should be worked on in tandem with reasonable accommodation that respond to individual needs when promoting accessibility.

*DEAI: DEAI is an acronym comprised of the first letters of the following four words: Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion. Launched in August 2023 as an activity of the National Center for Art Research, DEAI Research Lab conducts research on the concept of DEAI, which has become a global trend, and examines specific methods and requirements for raising the standards of museum accessibility. With participation from outside experts, in FY2023 the lab began to note specific cases and conduct activities to enrich understanding of reasonable accommodation in museums. For more information and explanations of the DEAI Research Lab and reasonable accommodation, please read the following article: Launch of the DEAI Research Lab and Reasonable Accommodation.

https://ncar.artmuseums.go.jp/en/reports/d_and_i/accessibility/post2024-1260.html

** ‘Museum(s)’ as used in this article includes not only art museums but also museums of the humanities such as archaeology, history, folklore, and literature museums; natural science museums devoted to natural history and science and engineering; aquariums; zoological and botanical gardens; and archives and memorial museums.

Introduction—My Encounters with Art Museums

I have been working as a staff member at an NPO involved with disabilities in arts and culture for 27 years. I participate in the DEAI Research Lab. to share modes of thought and practical knowledge related to reasonable accommodation as viewed from the perspective of people with disabilities. The case I present here includes the worries held by people with characteristics of hyperesthesia, how the projects I was involved in received these concerns, and the trial-and-error process that this initiative underwent. It is not what could be called a “museum case study.”

To start, I will write about myself, and this may be the first time I put this down in writing as an NPO staff member. My origin story is that my family member has a disability. I learned and grew up in the same environment as my brother, who is one year older than me. We walked the same path to school, from nursery level through elementary and junior high school. This experience affected my sense of humanity and my thinking. When I was a high school student, I learned that my brother had an “intellectual disability.” At the time, this was revealed when my older sister, who worked part-time at a children’s welfare centre, convinced our parents to give him an IQ test. For me, my brother would be no different regardless of whether he did or did not take the IQ test. However, I think I was perplexed by how our future paths and options in life would diverge.

Burdened with these perplexing thoughts at the height of puberty, the perfect refuge for me was the art museum. Within walking distance of my high school was the Miyagi Museum of Art, and visiting it and meeting residents gathering there was what decided my future path. Going to the art museum and coming into contact with the mysterious citizens that gather there (who I later found out were curators and artists involved in the founding of the museum), I gained an interest in pursuing ways to leverage the value of arts and culture in people’s lives and in the local area.

I continued my studies at a fine arts university, and with some influence from art management and regional art festivals that were starting to gain attention at the time (the 1990s), I participated in and experienced various exhibitions and festivals. But for some reason, what fascinated me were the artistic activities of everyday people who did not call themselves artists. This is how I came to be involved in managing studio activities for children with disabilities, which I approached the university to allow them to use the facilities for studio activities.

“What kinds of possibilities do the arts and culture have for people, and for society?” The focal point of my interests gradually developed, and I spent over a year doing research in Japan and overseas. I then stumbled upon the perfect place for me, a group focused on disabilities and arts and culture, which is where I continue to practice today2).

The “Quiet Hour” Initiative Sparked by Considerations of Hyperesthesia

I first became aware of the issues of people with symptoms of hyperesthesia in around 2017. When The Nippon Foundation DIVERSITY IN THE ARTS Exhibition3) was launched, I participated as a member of the accessibility team.

One morning, the TV news mentioned that a supermarket in the UK was experimenting with introducing a “quiet hour” (translated as “silent hour” or “peaceful hour” in Japanese). Before opening, the store would lower the intensity of its lighting and turn off the audio on its various image display screens, as much as possible, and welcome customers with hyperesthesia. Those who were interviewed included some who stated that they had developmental disabilities.

Up until that point, I had encountered issues related to hyperesthesia several times in my everyday activities. For example, I had encountered people who became unwell in crowds and needed a place to rest, people who were unable to shop at large-scale electronics shops because the glaring lights and extremely loud announcements caused them distress, people who could not ride buses due to their sensitivity to certain smells, and people unable to participate in social life at all without the use of headphones for noise reduction.

How do people with hyperesthesia symptoms such as these perceive places like museums, and how do they access exhibition spaces? While thinking about these questions, the exhibition theme was set to be “an accessible art museum open to all types of people.” Accessibility inspections and preparations were already underway regarding making the space physically barrier-free and accessible to people with visual or hearing impairments, and when I proposed finding an approach for people with hyperesthesia symptoms, which we had not yet worked on, we ended up provisionally introducing such an approach during the exhibition period.

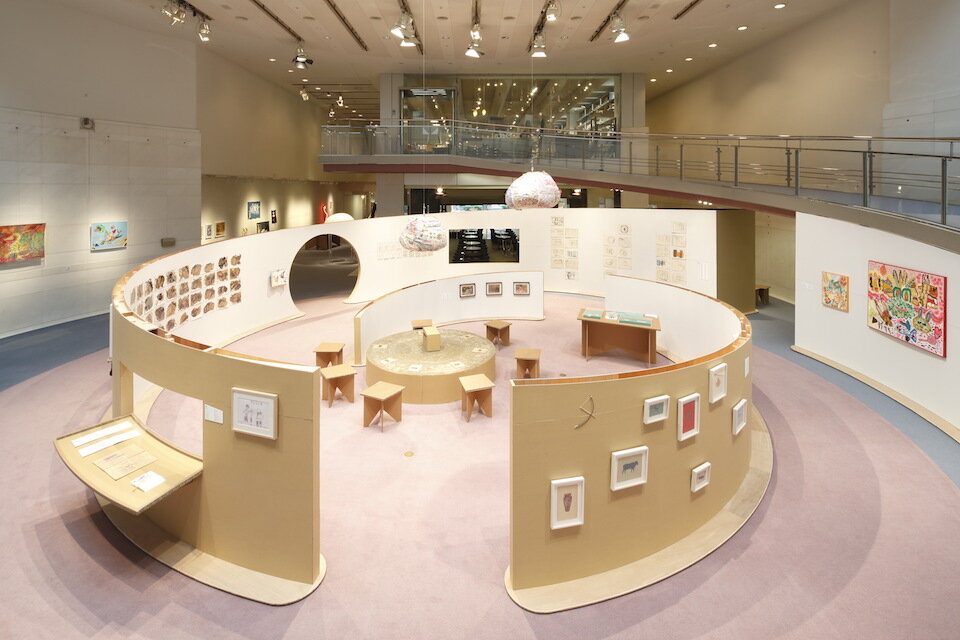

2017 The Nippon Foundation DIVERSITY IN THE ARTS Exhibition “The Museum of Together” Spiral Garden venue (photo by Kioku Keizo)

I was able to See My Favorite Artists’ Works! Thanks to “Quiet Hour”

Right up until opening, we carefully checked all the points of concern and worked to prepare for people with hyperesthesia symptoms. The results were the following two outlines of plans that were implemented (text is the same as the original for the event).

This is a special art appreciation session held outside the regular museum hours, primarily for people who have intellectual, developmental, or mental disabilities and oversensitivity to sensations and perceptions.

Date and Time: Tuesday October 17, 2017, 9:00-11:00, to Tuesday October 24, 9:00-11:00

Place: Spiral Garden (1st floor)

Visitors: Anyone can attend, but the event is targeted towards those who wish to appreciate the artworks in a quiet venue, with the lighting lowered to a minimum and the noise levels reduced in the gallery.

Capacity: 30 people per session (in order of arrival)

Participation fee: Free

Quiet Room

This exhibit provides a room in which you can spend time quietly within the exhibition venue. Please do not hesitate to reach out to the staff if you need to use this space when you want to calm your nerves, or if you feel mentally or physically unwell.

A “quiet room” set up at the venue (photo by Kioku Keizo)

I remember that about 10 participants showed up for each session of the “quiet hour” initiative. A few of these groups I remember distinctly. One couple with mental disabilities, who were art fans, told me “Since we don’t like crowds and feel anxious about other people watching us, we really enjoyed getting to see the exhibit comfortably in a space with the lighting and noise brought down to a minimum.” A mother of a child with disabilities told me her impression of the event, saying “There were works that we could touch, and we got to calmly tour the venue at my child’s pace, thanks to staff members joining us.”

One person said, “I could come to see my favorite artists’ works, thanks to ‘quiet hour’!” When I asked about the details, I found out that that one person had come to visit from Fukuoka, and given her sensory characteristics, she had given up on going to Tokyo, much less attending an exhibit so crowded that it needed admission restrictions. However, she made up her mind when she found out about this “quiet hour” and succeeded in overcoming various hardships to get there.

Not Quiet at All—Surfacing Issues and Improvements

On the other hand, we received some harsh comments from participants at the first session of the “quiet hour.”

One had to do with the large number of staff and excessive interference. Wanting to see this first initiative, organizers and venue managers and staff came to observe, and in due course their gaze drifted to the participants. Staff members also tried to communicate with the best intentions in mind, but some people found this excessively meddlesome, and wrote on their surveys “It was not quiet at all.”

Furthermore, there were also issues related to the environment that had been prepared for the “quiet room.” One proposal was to use the breakroom area that already existed in the building itself, but that would have given rise to the issue of it being far away from the exhibition venue. We then thought it would be best for people to be able to use the space in a psychologically safe-feeling way, at a closer distance if possible, so that venue staff could respond immediately; thus, the space was set up within the venue space. However, because there was a storage area for the luggage of the volunteer staff at the back of the “quiet room,” there were many people coming and going, and users commented that they were unable to calmly make use of the “quiet room.”

Ahead of the second session, the team assessed what improvements they could make. We even directly emailed some of the people with hyperesthesia who had completed the survey to ask them some questions.

We started by telling the organizers and venue managers about the opinions and concerns of those involved and arranged to fix the environment of the venue. For example, we limited attending staff to those with deeper knowledge of hyperesthesia and asked organizers to limit the presence of those observing or doing research. In this way, cooperation not only from the staff directly involved, but also from people involved in all sectors and departments of the exhibition, was indispensable. This kind of encouragement helped promote collaborative thinking, in which the management side also found points for improvement.

Regarding the quiet room space, we prepared an “occupied” sign card so that only staff who were well-prepared to provide care would enter the room when that sign was posted. We also handled the issue of the gathering space and luggage storage for volunteers by moving this to another location during the “quiet hour” sessions.

Furthermore, after the second “quiet hour” session was held, we prepared a new project called “Enjoying Exhibitions: Brainstorming with People with Intellectual, Developmental and Mental Disabilities!” Interested parties and supporters were invited to attend, and people who had largely “invisible” disabilities such as hyperesthesia, and people who had never even been to an art museum or exhibition, were asked about the kinds of perspectives that were needed, and gave time to speak directly. Interested parties with mental disabilities and staff of welfare facilities supporting people with intellectual disabilities spoke about their experiences. Curators of education for art museums came in from across the country, and independent curators joined as well, creating a valuable opportunity.

Looking Back on Past Activities

After the exhibition, I met Takahashi Hidetoshi (working at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry at the time, now working at Kochi Medical School), who had conducted prior research on people with hyperesthesia. He gave me the following comments on the topic:

・In light of international standards, Japanese society has a high level of environmental noise from the start, and this has a negative effect on children’s development.

・Hyperesthesia is found not only in people with developmental disabilities, but a certain number of cases can be confirmed in the general population as well.

・Biologically speaking, people with developmental disabilities often have hyperesthesia.

・Policies and approaches for dealing with sensory issues are now referred to as “sensory friendly”; the space we called a “quiet room” would be more appropriately titled a “sensory-friendly room.”

・Far more practices such as these should be implemented in Japan.

In the UK case example that I saw on the news in 2017, one of the things that won me over was that the supermarket had better sales results in this experimental period, showing that this service had value even from a business angle. Even in Japan, considerations for people with hyperesthesia symptoms are starting to be implemented at soccer fields, supermarkets, and cultural facilities such as theatres and concert halls, and even at social educational facilities such as zoological gardens and aquariums.

Even at our NPOs and related organisations, we have several examples of key activities we have implemented in the past: establishing a community centre at a welfare facility that opens with art (2004), creating a project to license works by artists with disabilities (2007), managing an intermediate support organisation for disabilities and arts and culture following the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011), and establishing the “Good Job! Center” that uses art and design fields to propose work styles for people with disabilities (2017). The common thread of these activity themes is “creating something new alongside people with disabilities.” Running activities centred on people with disabilities gives us an awareness of the physical sensations we have as human beings, and I think that being aware of this will enrich our society. The fact that museums and cultural facilities, including art museums, are an instrument and vessel for this is something that I hope to continue to convey through our current space of practice, “Museums for Everyone”4) .

Notes

1) Hyperesthesia is a condition in which the senses (hearing, sight, smell, touch, and taste) are very sensitive, causing difficulties in everyday life. Depending on the person, issues can include panic attacks due to direct sound or light, or having very strong fixations about certain sensations.

2) Involved in Tanpopo-No-Ye (Nara) (1997-2011), comprised of three organizations: Tanpopo-No-Ye Foundation, Wataboshi-No-Kai Social Welfare Corporation, and Nara Tanpopo-No-Kai. Later transferred to related organisation ABLE ART JAPAN (Tokyo), opening the Tohoku Office (2012) and continuing to work there (2012-present).

3) The Nippon Foundation DIVERSITY IN THE ARTS Exhibition “Museum of Together” (October 13-31, 2017, Spiral Garden, organizer: The Nippon Foundation)

https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/moto

4) “Museums for Everyone: The Museum Access Center Program” is an initiative that aims to facilitate access to museums for people who have difficulty in visiting art museums and other museums, and to allow all kinds of people to have richer experiences at museums. ABLE ART JAPAN drives these activities jointly along with interested parties who have disabilities.

https://minmi.ableart.org